A few weeks before lockdown I was able to open our new mineral display. It was a great opportunity to show off our stunning gemstones, gold and diamonds. More importantly it was a chance to tell some of the hidden stories of how we got the collection and the people involved. The history of Black and Indigenous peoples, and the role of empire in museum natural history collections is largely unknown or ignored. Since finishing the display, I’ve had chance to uncover more information and think about how museums need to change going forwards. This post is the second about Manchester’s Minerals and Empire.

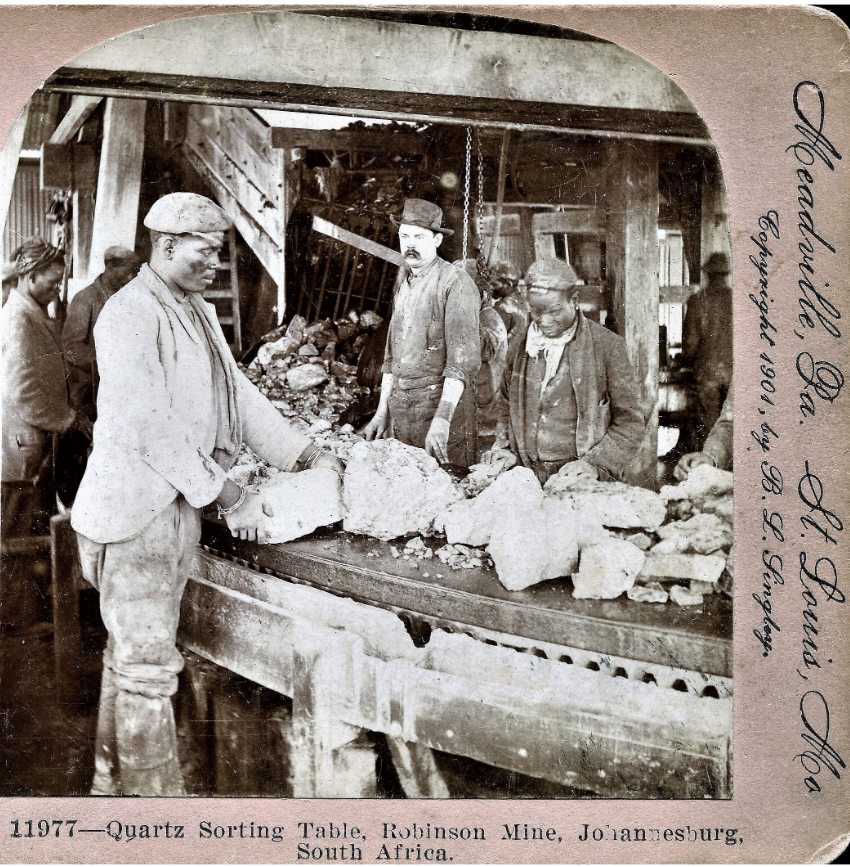

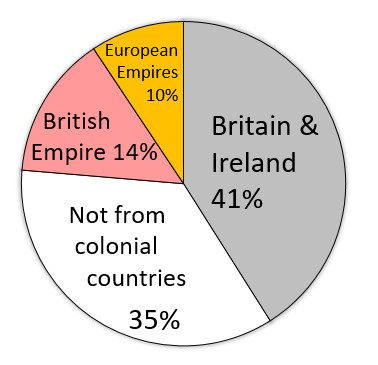

Part of what I wanted to do with this research was to uncover the stories of the people who had mined our minerals, but I also wanted to try and test if our minerals were an attempt to map the resources of empire. Data analysis of the mineral collection shows that 24% of the collection comes from countries that were previously colonised.

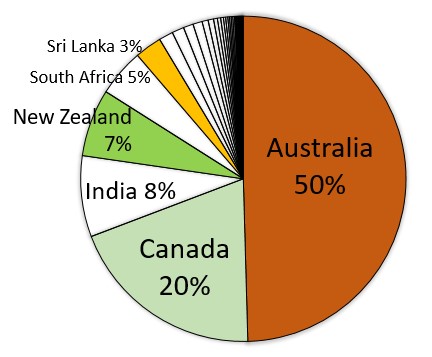

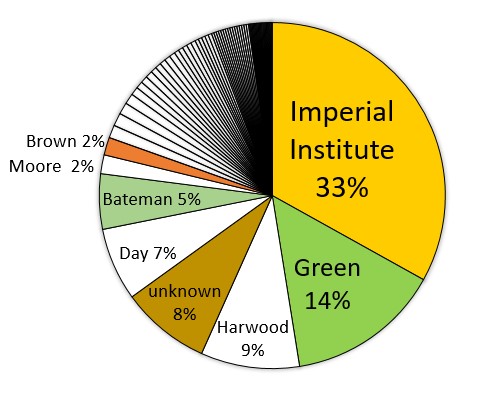

50% of the Museum’s minerals from the former British Empire are Australian, of which 33% came from the Imperial Institute.

The Imperial Institute was founded in 1887 to commemorate Queen Victoria’s jubilee. The main idea behind the Institute was for it to be ‘a centre and clearing house for information investigation and exhibition of the natural resources of empire’. It was a forerunner to the Commonwealth Institute.

The transfer of minerals from the Imperial Institute to Manchester Museum was probably part of the Institute’s efforts to reframe the collection and a shift from the original colonial objectives. The decline of the British Empire had caused the organisation to re-evaluate its purpose to become focussed on display and education rather than research.

This analysis has shown that Manchester Museum’s mineral collection is intimately connected to empire, but the history of Black and Indigenous peoples is ignored or unknown.

There are enormous opportunities to develop this work through fostering partnerships with source communities around the world. This research is a call to action for all museums to uncover and tell these stories and be open about the role of empire in our collections.

I gave a presentation about this work at the Natural Science Collections Association ‘Decolonising Natural Science Collections’ conference.

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment